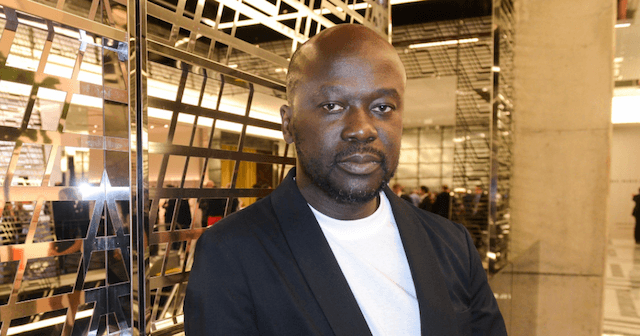

Chef Eric Adjepong is unarguably a Top Chef masterpiece. He was eliminated in season 16’s finale of the cook show, after presenting the first course of a meal inspired by the transatlantic slave trade to judges who ultimately favoured a menu drawn from “summers in the south.” However, Adjepong went on to cook a version of his menu to a sold-out crowd at Tom Colicchio’s Craft in New York City, and hasn’t stopped building since.

With projects ranging from Pinch & Plate — the full-service dinner party company he co-operates with his wife, Janell — to hosting Food Network’s Alex vs America, to his historic two-book deal with Penguin Random House, Adjepong has stepped fully into the spotlight. And where he goes, so too is the specificity and resilience of West African diasporic cuisine moved front and centre.

His forthcoming cookbook Sankofa is a necessary composite of memory work, education, and encouragement, refracting Adjepong’s distinct perspective as a Ghanaian-American chef raised in the Bronx, now based in Washington, D.C., into a stream of traditional West African recipes and an invitation to improvise, or “play jazz,” as he puts it: an apt metaphor for the magic that occurs where classical training meets liminal experience.

Veronica Fitzpatrick of Sharp Magazine recently spoke with Adjepong through Zoom:

I’m so curious about the various professional hats you wear, from the notoriety of TV hosting on Alex vs. America to in-person dining, where you’re not necessarily always as on display as the food itself. What’s it like moving through the worlds of food and food media in such diverse ways, from centre stage to “back of house”?

I’ve never thought about it that way, like front of the house/back of the house. I love hospitality, probably as holistically as possible. When I say that, I mean in all regards: as granular as how a guest feels when they sit down, the ambiance — it’s the lights that are on the table, how low the seating is, and the darkness and the mood and the smell and the colour, all that plays into an experience.

I stick to what I’m good at; I’m not doing anything that’s far-fetched or out of the pocket, so for me, in this path that I’m on, it all kind of just makes sense. And I’m not forcing anything.

In-person dining strikes me as an experience where you get to potentially exercise control over all these variables, but then on television, it’s such a collaboration. You’re at the mercy of editing — Yes! — and everything!

My ignorance was so high before hopping into the TV space. It’s a true production. There’s an audio team, a visual team, there’s a culinary team, there’s an art department, and when you put them all together, it’s like busybodies, ants, moving all around. It makes sense if you think about the brigade system in the kitchen, the hierarchy: you have your executive chef and your sous chef and line cook, and you kind of have the same thing behind the scenes, with all the people who are moving strings.

It’s not every Top Chef alum who’s able to spin upward into a more extended television career.

Very much so. I was just happy to make it past episode three. Now all of this has happened, I really had no idea, nor did I call it, but it’s the power of saying yes more than no, and just being in good spots, and a little bit of luck helps as well. All that.

Tell us about your upcoming cookbook, Sankofa.

I’m finding out stuff about myself, and I’m having to call my sister and my mom to explore stories from when I was a kid that I didn’t remember, and oddly enough, it becomes therapeutic. I’m going back and I’m literally telling my life. Sankofa means “it’s not too taboo to go back and fetch for something.”

San means to return, ko means to go, and fa means to seek and look for. So, it’s not too taboo to fetch something at the risk of being left behind. I really love that message. It’s an Adinkra symbol, and Adinkra symbols come from the Ashanti Region in Ghana where my family is from.

What ingredients or flavours would you suggest home cooks experiment with to activate aspects of the palate intuitive to West African diasporic cuisine?

When I think of West African diasporic flavours, the Caribbean islands, West Indies, even South America and the American South, I think of warm spices. Cinnamon, clove, allspice, nutmeg. I think of aromatics: ginger, garlic, and then maybe a little bit of heat from habanero.

They grow almost invasively so we use them to our advantage. I also think of preservation, salting and pickling, and the umami — almost like the funky fish sauce vibe as well.

Rewatching your seasons on Top Chef, thinking about you introducing diners or judges to unfamiliar flavour profiles or textures, I kept thinking about this quote by the Senegalese writer/filmmaker, Ousmane Sembène. He had incredible success internationally, but he’s often cited as saying (I’m paraphrasing), “Africa is my audience, the West and the rest are my markets.” How do you balance a sense of authenticity — as contested and personal and subjective as that is — with wider accessibility? Who is your audience?

Kind of how you notice your speech may change depending on what group of people you might be around, a different community, right? You’re not going to talk the same to your students that you would to your best friend, or your mom. So the food that I cook — I approach it in the same way. Perfect example: eating any sort of steak rare or mid-rare might be super crazy in West Africa, right?

Everybody eats their steak well-done. Versus in the States, medium rare. If I serve a sauce on a well-done steak, it needs to be a looser sauce, if I’m serving that same sauce on a rare steak, I may have to thicken it up. I’m serving an audience that’s used to the food, I can go in with a little bit more unabashedness.

A dish that signifies novelty or discovery for one diner may be more about recognition or resonance for another.

Especially in a competition. When I first got in and got the word and knew I was going to be on, I’d worked in Peruvian, modern American, French, was classically trained at Johnson and Wales, but I knew if I had the opportunity to make West African food, well — the continent being the second biggest continent in the entire world and the food being so unknown didn’t make sense to me.

The fact that this show is so prestigious, 16 years in, and I haven’t seen a chef cook anything from the continent — I was like, why not me? Let’s just do it. It was a huge risk because I could’ve been eliminated the second day. But Padma [Lakshmi] mentioned this as well: I was not only cooking, but teaching throughout the season.

At the end of the day, the food needed to taste good. I won a dish with fufu, a very traditional, extremely West African meal that’s never been changed since the day it’s been invented. And I served it to a bunch of people who’ve never had the dish before, and I won that challenge. So it proved that it could happen, and people are open and willing to eat. I know there was a big push for people to bring new voices and new judges to the panel after that as well, and I thought that was awesome. I really agreed.

In so many ways, even though the title’s not mine, I definitely feel like I won.

Source: Sharp Magazine

READ ALSO: These Chefs Are on a Mission to Decolonize West African Food

Abeeb Lekan Sodiq is a Managing Editor & Writer at theafricandream.net. He’s as well a Graphics Designer and also known as Arakunrin Lekan.