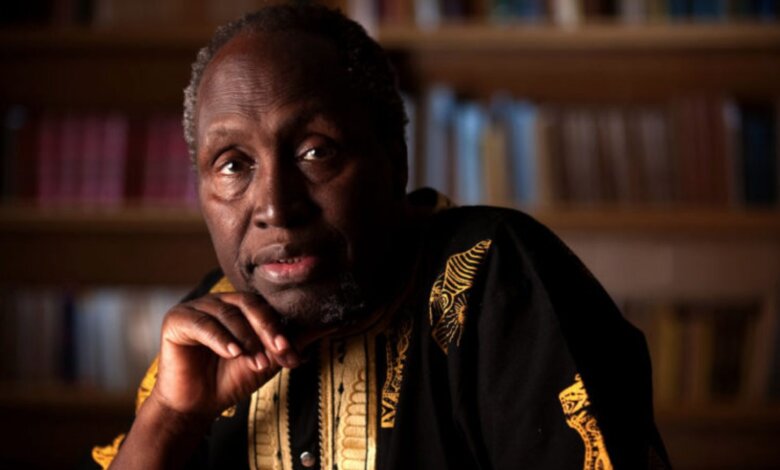

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, a revolutionary of African literature, dies at 87

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, a revolutionary voice of African literature, has died at age 87 in the United States after a long illness. His legacy, however, burns bright as a celebrated figure whose words refused to be caged by prisons, silenced by exile, or diluted by colonial tongues.

For nearly 60 years, the writer, scholar, and activist used his powerful works to advocate for African identity, decolonization, and the use of indigenous languages in literature. From the depths of colonial Kenya to the challenges of post-independence leadership, his writing, searing, poetic, and unflinching, became a mirror for his homeland and a megaphone for the continent’s conscience.

Born in 1938 as James Thiong’o Ngũgĩ in Limuru, Kenya, during the oppressive grip of British colonial rule, he was raised by a farming family who scraped together enough to send him to Alliance High School. His youth was shaped by the brutality of the Mau Mau uprising. His was village razed, and his family imprisoned; his deaf brother, Gitogo, was also shot dead by a British soldier for not hearing a command.

Ngũgĩ’s personal tragedy became an unbreakable resolve for him. While at Makerere University in Uganda, he shared his first manuscript with Nigerian literary giant Chinua Achebe. His debut, Weep Not, Child (1964), became the first major English-language novel by an East African, bringing the rise of a new literary voice.

Ngũgĩ’s early success was followed by A Grain of Wheat and The River Between, solidifying his status as a literary force. But 1977 marked a pivotal turning point, he abandoned his Christian name, James, and chose to write exclusively in Kikuyu, his mother tongue, in an act of radical reclamation. His novel Petals of Blood launched a scathing critique, not of colonialists but of Kenya’s corrupt post-independence elite.

That same year, he co-authored the revolutionary play Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”), which ignited the fury of the Kenyatta regime. For his boldness, Ngũgĩ was imprisoned without trial. Yet, even in a maximum-security cell, he refused to be silenced, writing Devil on the Cross on toilet paper when no notebook was allowed.

After his release, he faced an assassination threat and decided to exile over silence, living abroad for over two decades. When he returned to Kenya in 2004, he was met by cheering crowds, but also by violent attackers. He and his wife, Njeeri, were brutally assaulted in what he believed was a politically motivated message.

Despite the trauma, Ngũgĩ never stopped teaching, writing, and championing African languages. From Yale to UC Irvine, he became an academic torch-bearer, challenging the global literary establishment with his seminal essay collection Decolonising the Mind. In it, he boldly questioned why Africa should cling to the languages of its colonizers, even if that meant confronting former allies like Chinua Achebe.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o received numerous honours throughout his life for his literary and political contributions. He was awarded the Nonino International Prize for Literature in 2001 for his lifelong commitment to cultural resistance. His novel The Wizard of the Crow earned him the NOMMO Award for African Speculative Fiction.

He also received the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Africa, and was made an honorary member of the Ethiopian Academy of Sciences. Although he never won the Nobel Prize, he was widely recognized as a perennial nominee and one of Africa’s greatest literary figures. He received honorary doctorates from leading institutions such as Yale University, the University of Leeds, the University of Dar es Salaam, and New York University.

Ngũgĩ also held prestigious academic positions, including Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine. His work in defence of free expression was acknowledged by PEN and other international organizations.

He leaves behind nine children, four of them published authors, and an unmatched literary legacy. As his daughter Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ shared, “He lived a full life, fought a good fight. As was his last wish, let’s celebrate his life and his work.”

Written by Kweku Sampson

This article is published by either a staff writer, an intern, or an editor of TheAfricanDream.net, based on editorial discretion.