Shatta Wale: the 21st-century African griot by Agana-Nsiire

In West African tradition, griots were more than musicians; they were custodians of history, culture, and moral guidance. They carried the stories of communities through oral narratives, music, and instruments like the Kora, Koolgo, Mbira or Lunga, ensuring that every event, every triumph, and every lesson was remembered.

Griots played to farmers, to villagers, to everyday people, narrating struggles, victories, and social commentary, all while entertaining and motivating their communities. Shatta Wale fits perfectly into this role.

His music inspires, motivates, and records the lived realities of Ghanaians, transforming struggle into lessons and victories into collective pride. His songs ignite a fire, giving listeners the courage to act, the energy to push forward, and the wisdom to reflect.

First stint

Shatta Wale first appeared on Ghana’s music scene in the early 2000s under the name Bandana, releasing hits like Mokoho. He learned harsh lessons from the industry during that period, feeling exploited, he walked away from his contract cleanly, opting for independence.

For over a decade, he went underground, studying, learning, and refining his craft. By the time he returned in 2012–2013, social media was beginning to reshape the music industry.

Shatta Wale leveraged Facebook to release his music directly, slowly building a following that would soon explode nationwide and be known globally as the Shatta Movement (SM) Empire. His reintroduction came with the anthem “Dancehall King”, which he produced, reintroducing himself as not only an independent Hitmaker but a producer as well.

The song quickly became a street hit, resonating in areas like Nima, Newtown, and Kolegonor, and went on to become a commercial success nationwide. From there, he dropped “Everybody Like My Thing” and an endless stream of hits, cementing his place as Ghana’s most prolific and influential dancehall artist.

Motivator and cultural commentator

Shatta Wale’s genius lies in his ability to motivate through music. Songs like ‘Prove You Wrong’ and ‘On God’ narrate struggle, resilience, and triumph.

He credits mentors and icons such as Kofi Abban (CEO of Rig World Ghana), late legend Daddy Lumba, hiplife icon Tinny, as well as comrades from his journey in the streets such as Solash, Juweid, Salty, Deportee, Fa Rovers, Cyborg, Volcano and more, demonstrating how acknowledgment and respect are central to his philosophy.

Griots didn’t just tell stories back in the day; they also called out injustice through their rhetoric. Similarly, Shatta Wale does the same with a self-reflective approach. Yes, he states injustice as a fact, be it from the government or the music/media industry. Still, he emphasises even more the duty of listeners to take responsibility for themselves, and not just blame leaders.

In Ayoo, for instance, he declares, “nobody dey fit talk, we dey kill our future, Ayoo!” a call to action against passivity, the lack of courage to speak up, and complacency.

In the song ‘Prove You Wrong’ he declares, “I will always be a fighter…” then goes on to enquire of the Ghanaian public,“…why should i always apologise for the monster I’ve become,” a tag attached to him for his unapologetic public tantrums on issues that affected him and his industry peers who lacked the courage to speak up.

He further asserts on the song,“…no one ever apologised for making me this way/ go ahead and doubt me/ go ahead talk about me/ …I will ALWAYS PROVE YOU WRONG”

It is undeniable that through his sometimes triggering advocacy, Shatta Wale has used his voice and music as a weapon to bring reform, education, inspiration, and mobilisation of the youth, giving Ghanaians, and Africans more broadly, a sense of agency and purpose.

Struggles, industry battles, and social accountability

Shatta Wale has fought against industry exploitation, unfair payment structures, and systemic bias. He was one of the first artists in Ghana to demand fair settlement fees for local acts alongside international performers on Ghanaian stages, shifting the financial landscape for the entire industry.

From boycotting shows to reconciling publicly with adversaries, Shatta Wale uses music and action as his response mechanism, and lets humanity serve as his compass. He calls a spade a spade, and then it is back to business.

A typical example of proof that he holds no grudges after voicing his grievances with any entity can be seen in the recent turn of events when he organised the extremely successful Shatta Fest in October of 2025. Leading to the event, he made amends with Charter House – after being at loggerheads for a decade – and collaborated with them on the production of the historic festival.

He even paid them a public courtesy call in a show of appreciation for their support and solidarity in their reunion. This showed a side of Shatta that the industry may have been overlooking.

Perceptions, however, seem to be shifting after this public reunion, and the industry appears to be taking a liking to the King of African Dancehall once again, actively rallying behind him to help cement his legacy in the Global entertainment space. Yes, confrontation can coexist with diplomacy, and after disagreement, amended action should follow, not enmity.

Songs that shape a movement

Shatta Wale’s catalog is a chronicle of Ghanaian life, from street anthems like Minaminio Sin to motivational tracks like I Am Not Going to Jail This Year (IANGTJTY). In IANGTJTY he addresses the harmful effects of doomsday prophecies targeting artists, and calls out law enforcement for inaction and bias in what led to the ‘On God’ hit maker spending two weeks in prison.

Although the Dancehall Legend was blamed for bringing the arrest upon himself by falsely claiming to have been shot (as one of the prophecies predicted) to make a point, eventually the issue was addressed and the doomsday prophets were silenced. Once again, all thanks to the courage of Shatta Wale.

However, being arrested for causing fear and panic in retaliation to those who caused you and your loved ones fear and panic, but didn’t get arrested, doesn’t seem fair does it? Thus the track IANGTJTY was birthed to set the record straight, and “Close the Matter”.

Beef, media, and billboard recognition

When Shatta Wale decides to make a media nay-sayer a scapegoat, he navigates the confrontation with unmatched skill. In “Who Send You?”, he addresses media pundit Highest Eri directly after a public banter between the two. The song’s title questions who authorises negative narratives and why.

It was featured on Billboard, marking international recognition for a track born from local conflict. Shatta has always blamed the negative posture of Ghanaian media reports on the entertainers in the industry for the limitation that musicians face in their pursuit to penetrate the global stage.

He repeatedly tells the story of how a customs agent at an international airport googled him to confirm his background and only found a thread of negative headlines about him. He cracked a joke to her about it and got away with it b,ut he cites that example to wake local journalists up to the impact of their reporting on the global scene.

Recently, he has jokingly declared himself as the media policeman to ensure the right thing is done, but with a hit like “Who Send You?”, it seems Shatta is not joking, and means business as usual.

Fans and observers on X (Twitter), upon reviewing the Billboard article on the Song, praised Shatta Wale’s authenticity, highlighting how he transforms personal and professional disputes into archival music that resonates far beyond Ghana’s borders.

As one X user put it, “Local champion getting international recognition more than the international champion”. Critics’ predictions of failure were rendered irrelevant; the song charted, trended, and became another testament to his griot-like mastery.

Global recognition and cross-cultural impact

Though a dancehall artist, Shatta Wale remains fiercely Ghanaian as he blends Jamaican raga, patois, and global dancehall rhythm with Ghanaian languages—Ga, Ewe, Hausa, and Akan—without diluting the essence of his identity.

His collaborations with global icons include global Pop Icon Beyoncé selected Shatta Wale for her album, The Lion King: The Gift, featuring him on the single, “Already / King Already”.

In the music video, which heavily features African artistry, Shatta showcases Ghanaian dancers led by Dancegod Lloyd, further projecting Ghana and Africa to the world, as he boldly displays the Ghanaian flag in the backdrop of his appearance with the pop Icon.

On another global feature with the acclaimed Dancehall King Vybz Kartel – affectionately known by other prominent dancehall artistes and fans as Di Teacher, Shatta Wale projects African history and wealth.

The title of the song is “Mansa Musa,” and on it, the African griot name drops Asantehene (the king of the Ashanti Kingdom in Ghana), trumpeting his reverence for Ghanaian royalty, and again proving he can shine on a global stage without abandoning his roots.

“On God”: the griot’s solo masterpiece

No song embodies the lonely road of Shatta Wale’s griot identity more than “On God.” Written, produced, and performed entirely by him, it combines personal faith, struggle, and victory.

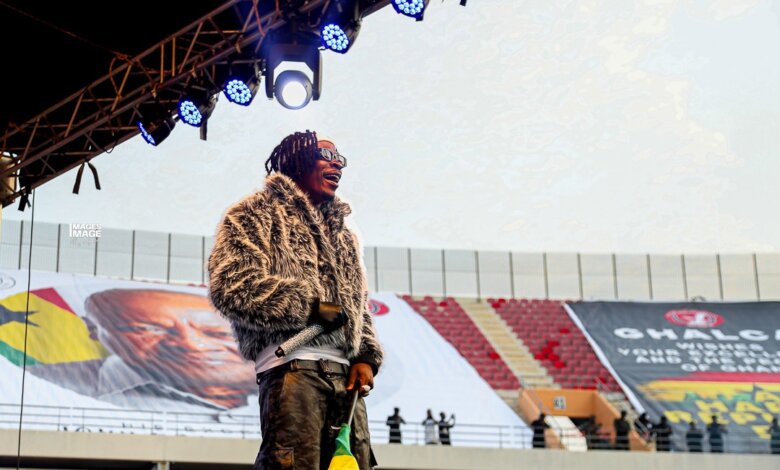

His 2025 performance at Vybz Kartel’s Freedom Street concert in Jamaica initially drew skepticism—how would Ghanaian Pidgin connect with a Jamaican audience?

The answer: profoundly. The song resonated deeply with the sold out stadium, went viral internationally, and became a global touchstone. Shatta Wale told a local story in a universal language of resilience and truth, proving the modern griot need not translate authenticity to be understood.

“You no know me, you for google/ I say this head bigger than your duku” is a line from the song that plays on a triple entendre of the word head, first as the idiom of a swollen head, second as the head of the dancehall/music industry in Ghana, and third as a headline, since he is always in the news.

In all three instances he claims to be bigger than a duku (an african female head-gear that adds tremendous volume to the size of a woman’s head when worn).

His creative process mirrors traditional griots: he releases music when life demands it, without a pre-set plan, album calendar, or formula. Songs arrive organically, unpredictably, but always relevant. This immediacy, responsiveness, and autonomy are core to griot culture.

Counter-argument

Critics argue that Shatta Wale’s focus on Ghanaian pidgin, nontraditional release schedules, or confrontational style limits his appeal. Yet every milestone, Billboard recognition, viral tracks, Beyoncé collaborations, and global streaming success, demonstrates the opposite. Authenticity, immediacy, and cultural rootedness are not obstacles, in retrospect, they are bridges that make his music globally resonant.

On the flipside, when he chooses to, Shatta is able to turn on his Shakespeare persona and hit melancholic notes with purely English ballads to spew hits like Street Crown. The song, which was produced by Di Maker (Shatta Wale’s producer persona) featured a vulnerable side of the Street King.

It tells a story of the scars and silent battles that he contends with without ever breaking down as he stands up to the titans he goes against. The timing of the song’s release coincided with another detention of Shatta by Ghana’s Economic and Organised Crime Office, as part of investigations into a ring involved in the importation of stolen cars.

Shatta Wale’s Yellow Lamborghini Urus was fingered and seized, followed by his detention for about 24 hours. This time, however, Shatta was detained right at the backyard of his constituency and in no time, the entire communities surrounding Accra Central gathered around EOCO, literally pleading for his release. The crowd protested the unfair nature in which he was being treated without evidence of any crime.

The show of love was magnificent, and the euphoria surrounding the spectacle spread far and wide. Street Crown instantly became the anthem of the moment. It invoked the emotions of peers, fans and pundits who somehow found their voice this time around and stood up for the Dancehall king. The song broke international barriers and once again, earned Shatta Wale a feature with Vybz Kartel.

The ‘World Boss’ who had recently been released after serving over a decade in prison himself, resonated with the moment and the song and produced an emotionally captivating verse to serenade what is now the official Street Crown remix .

The pain and master craftsmanship of the two Dancehall Kings – one Global, one African – took the song to another level and further cemented Shatta Wale as a household name worldwide. Street Crown, which was considered for a Grammy Nomination but didn’t make the final cut, is not only a masterpiece and a classic, but also a stark reminder that Shatta Wale can be anything he needs to be, in order to be heard. Griot-vibes!

The 21st-century African griot

From his early days as Bandana to hits like Dancehall King, Prove You Wrong, Who Send You?, and the global phenomenon On God, Shatta Wale is a living archive.

He motivates, challenges, critiques, celebrates, and documents. He addresses injustice while holding communities accountable. He honours roots while engaging the world. He releases music that captures life as it unfolds, sometimes chaotic, sometimes explosive, but always true.

Shatta Wale is not just a musician; he is a griot, carrying Ghanaian stories, African identity, and universal truths to the world. Where traditional griots travelled villages and kingdoms, Shatta Wale travels the digital, global village, wielding rhythm, passion, and truth as his instruments.

Written by Adalba Agana-Nsiire

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in articles and content by our contributors are those of their’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of our publication. We make every effort to ensure that the information provided is accurate and up-to-date, while holding contributing authors solely responsible for their contributions.