Pre-colonial Zambian writing system revises African history

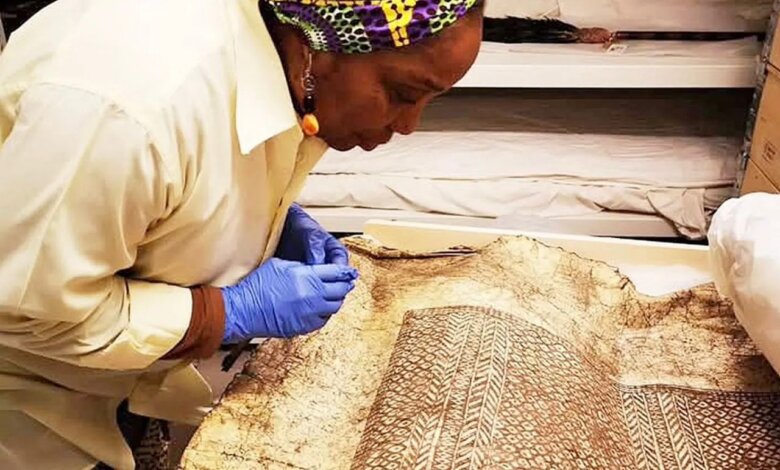

Photo: Mulenga Kapwepwe looks at one of 20 pristine leather cloaks in the Swedish archive collected during an expedition between 1911 and 1912 / © Women’s History Museum Zambia

A wooden hunter’s box etched with an ancient Zambian language has gone viral online not just for its craftsmanship, but for what it symbolizes, which is a long-overlooked African writing system. The box is part of The Frame, a social media campaign launched to revive women’s roles in pre-colonial Zambia and reclaim cultural heritage nearly erased by colonialism.

Fifty artefacts, including intricately patterned leather cloaks, ceremonial tools, and reed baskets, are featured, many collected during colonial times and now stored in foreign museums.

The idea took shape in 2019 when Samba Yonga, a co-founder of the virtual Women’s History Museum of Zambia, visited Sweden and learned that the National Museums of World Culture in Stockholm housed over 600 Zambian artefacts, despite Sweden never colonizing the country.

The collection, gathered by 19th and 20th-century explorers, includes ceremonial masks, fishing tools, and cloaks made by the Batwa people from antelope hide, worn by women to protect their children.

“We’ve grown up being told that Africans didn’t know how to read and write,” said Yonga to BBC. “But we had our own way of writing and transmitting knowledge that has been completely side-lined and overlooked.”

“These cloaks hadn’t been seen in Zambia for over 100 years,” Yonga says. “When we visited the original communities, no one remembered them. That knowledge was lost, frozen in museum storage.”

One of the most celebrated posts in the campaign features Sona (or Tusona), an ancient writing system used by the Chokwe, Luchazi, and Luvale people. Women once drew complex geometric symbols in sand, cloth, and on tools to encode messages about the cosmos, mathematics, nature, and community life.

“Sona went viral,” says Yonga. “People were shocked that something so advanced existed here and yet had been hidden.”

Another post, Queens in Code, shows a woman grinding maize on a stone. That stone, once buried with women after death, served as a tombstone, a symbol of her contribution to food security and family life.

Founded in 2016, the Women’s History Museum of Zambia is working to document and digitize women’s histories and indigenous knowledge. The team sees itself as modern-day archivists, piecing together what colonialism left fragmented.

“Our cultural memory was disrupted,” Yonga says. “But there’s a resurgence, people want to reconnect through fashion, music, even academia.”

Each artefact in The Frame is displayed within a literal border, a metaphor for how colonialism reframed African history. But this time, the frame offers context, not distortion. “This journey has changed how I see myself,” Yonga reflects. “Knowing my history, politically, socially, emotionally, has transformed how I show up in the world. And I hope it does the same for others.”

Written by Kweku Sampson, edited by Abeeb Lekan Sodiq

This article is published by either a staff writer, an intern, or an editor of TheAfricanDream.net, based on editorial discretion.