At the dawn of this century, the then editor of the Foreign Affairs Journal, James Fulton Hoge Jr., rightly observed that the global “transfer of power from West to East” was “dramatically changing the context for dealing with international challenges—as well as the challenges themselves” (Foreign Affairs, July/August, 2004).

MESSIANIC SENSE

In the Horn of Africa, the return to peace and collapse of sit-tight dictatorial regimes is spawning a major power shift.

It is also challenging Kenya’s influence in the region over the last five decades in a profound and palpable way.

The old regional balance of power that sustained Kenya’s regional influence rested on three pillars. One was a Strategic Alliance, a mutual defence pact ratified by the two countries in December 1963, with scions of the Solomonic Dynasty. The Kenya-Ethiopia Defence pact, which sought to curb the territorial and power ambitions of an increasingly militaristic and expansionist Somalia, ensured that Kenya and Ethiopia coexisted and collaborated in a duality of power as two regional powers with little competition for legitimacy or influence.

Second, this duality of power has rested on the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) established in 1996. Third, the Ethiopia-Kenya duality of power within IGAD gave the two powers a huge influence in the African Union and its Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). This enabled them to sustain the African Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) that has waged war against the terrorism in Somalia.

Sadly, this old regional security regime appears to be falling apart. The relative peace that has followed the end of civil wars in Ethiopia and Somalia in recent decades coupled with the thawing of historic power rivalries especially between Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia has shifted the axis of power to new alliances.

Power is gradually shifting to Eritrea and its allies in post-civil war Ethiopia and Somalia. Having emerged from the ashes of a long war of Independence against Ethiopia from 1961-1991, Eritrea is one of the few surviving nationalist and revolutionary regimes in Africa. It has a messianic sense of itself in the Ethiopia state, claiming a special contribution to ending the Ethiopia civil war and securing the post-bellum power.

ETHNIC SUPRMACIST

After defeating the Ethiopian forces in Eritrea, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) helped the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of Ethiopian rebel forces, to capture Addis Ababa and install a transitional government 1991. However, although Eritrea declared its independence and gained international recognition in 1993, supremacy wars and hostilities between EPRDF and EPLF sparked the Eritrean–Ethiopian War (1998–2000), a low-intensity border conflict (2000–2018) and complex proxy wars.

Click here to read other political stories

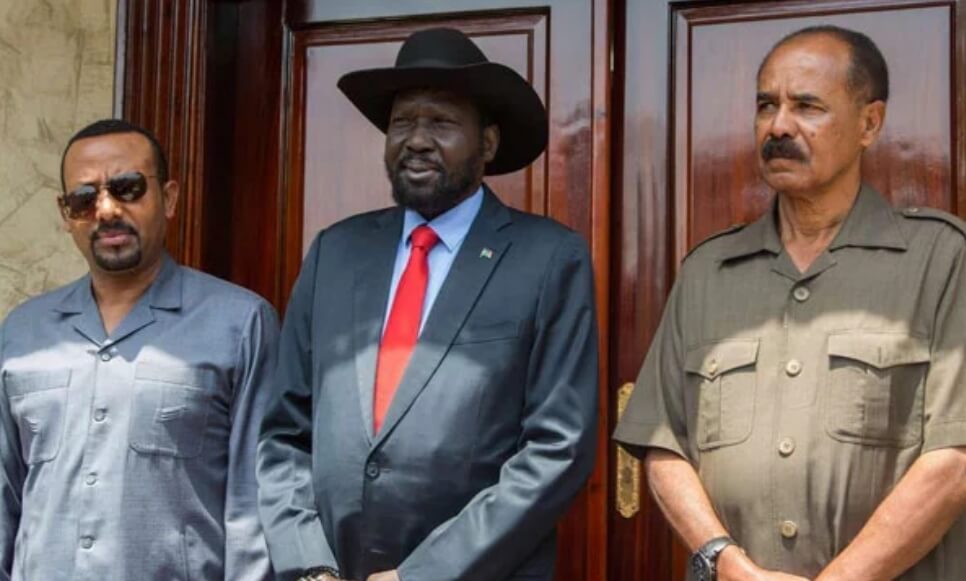

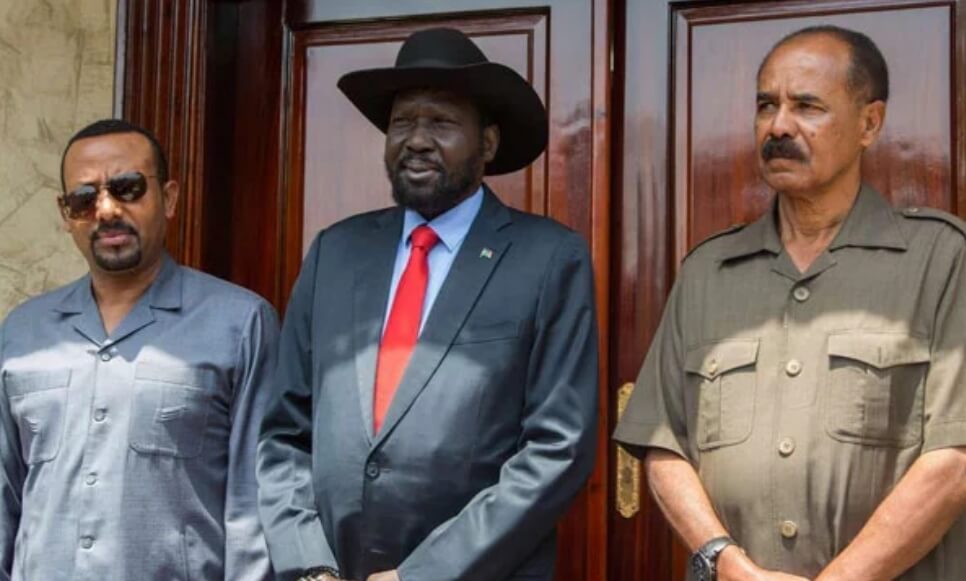

Three developments have shifted the axis of power in favour of a resurgent Ethio-Eritrea détente. One is the rise of Abiy Ahmed Ali as Prime Minister in Ethiopia and EPRDF leader on April 2, 2018 which paved the way for two powerful allies in the Ethiopian Civil War to join ranks in regional power politics.

Second, and related to this, on July 9, Afwerki and Abiy signed the historic 2018 Eritrea–Ethiopia peace pact, formally ending the border conflict, hostilities and proxy wars between the two countries, restoring full diplomatic relations.

Third, the election of Mohamed Abdullahi (Farmajo) as the President of Somalia in 2017, heralded the resurgence of ethnic supremacist politics inside Somalia and pan-Somali nationalism as the organising principle in Somalia’s regional relations.

After July 2018, Farmajo joined Afwerki and Abiy with the idea of a New Horn as the tie that binds the trio. The removal of long-time Sudanese strongman Omar El-Bashir on April 11, 2019 has left Afwerki as the senior-most leader and, arguably, the most influential figure shaping politics in the Horn of Africa. In a rare case where authoritarianism is aiding and securing liberal reforms, Afwerki’s Eritrea, touted in the media as “Africa’s North Korea”, is the guarantor of stability in Ethiopia.

TRIPLE DETENTE

Here, Abiy’s sweeping political and economic reforms have their discontents, especially Ethiopian Federalists and the Tigrayans—the ethnic partners in EPRDF who now feel that Abiy’s shake-up of the Ethiopian state is selectively targeting the Tigrayans.

Be that as it may, as power shifts to the triple détente in the ‘New Horn’, the future of Kenya’s influence as a regional peacemaker and guarantor of stability is coming into sharp focus.

The rise of the idea of the New Horn, largely hoisted on a pan-ethnic idea of “Cushitic Alliance” (Oromo and Somalis), has posed an existential ideological challenge to IGAD and the regional consensus it represents.

Second, Ethiopia and Eritrea—with its large fighting force remnants from its war with Ethiopia—are seeking a new role as a military ally to Farmajo. This raises serious questions regarding the future of AMISOM, especially its contingents from Kenya, Uganda, Djibouti and Burudi and the very war against Al-Shabaab terrorists.

Third, since the coming to power of Abiy (42), Ethiopia has enhanced its regional soft power, seemingly eclipsing Kenya as the lone regional peacemaker.

In the wake of the brutal crackdown on protesters in Sudan which left dozens of people killed on June 3, 2019, Ethiopia has stepped up its peace diplomacy. Indeed, Ethiopia has also moved to broker peace between Kenya and Somalia over the simmering maritime row.

Finally, and related to the above, power shift in the Horn has emboldened Somalia in its claim over Kenyan waters in what is unfolding as an existential challenge to the country.

Should the ICJ rule in favour of Somalia in the coming months, experts fret that Kenya will loose not only 62,000 square kilometres of its Indian Ocean waters.

It also risks losing access to international waters, effectively becoming a ‘land-locked’ country.

Written by PETER KAGWANJA

Oral Ofori is Founder and Publisher at www.TheAfricanDream.net, a digital storyteller and producer, and also an information and research consultant.